- Home

- Diana Lopez

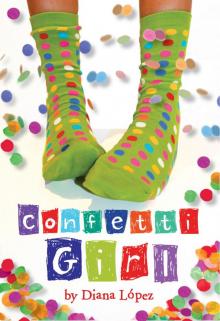

Confetti Girl

Confetti Girl Read online

Copyright

Copyright © 2009 by Diana López

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at www.HachetteBookGroup.com

Little, Brown Books for Young Readers is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

First eBook Edition: June 2009

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

ISBN 978-0-316-05252-8

Contents

Copyright

CASCARONES

1: 27-Pound Egg

2: Egg Therapy

3: Don’t Put Your Eggs in One Basket

4: Cascarones for Sale

5: Vinegar Stinks Up the House

6: Papas con Huevos

7: Scrambled Eggs for Brains

8: Cascarones War

9: Fragile as Eggshells

10: Cascarones Factory

11: Rotten Eggs

12: Egg on My Face

13: Egg Under the Bed

14: The Best-looking Egghead

15: Eat Quiche

16: Kidnapped Eggs

17: Stubborn as a Hard-boiled Egg

18: A Soggy Egg Salad Sandwich

19: Ms. Humpty Dumpty

20: Love Eggs

21: Dancing on Eggshells

22: No Eggs to Paint

23: Don’t Count Your Chickens Before They Hatch

24: Confetti Rain

GLOSSARY OF DICHOS

Acknowledgments

To Mom and Dad

CASCARONES

What are cascarones?

Festive, hollow eggshells, filled with confetti, that are cracked on people’s heads, scattering confetti all over the place and bringing everyone good luck!

How to Make Cascarones

Step 1: Buy a dozen eggs.

Step 2: Carefully crack eggs at narrow tip, keeping most of the egg intact, and pour out the yolks and egg whites.

Step 3: Gently wash the eggshells.

Step 4: Soak eggshells in a bowl with 1 tablespoon white vinegar, ¾ cup hot water, and 4–5 drops food coloring.

Step 5: Buy confetti or make your own by hole-punching used magazines or newspapers.

Step 6: After the eggshells have dried, pour confetti into the eggshell.

Step 7: Cut out circles of tissue paper and glue over the hole.

Step 8: Quietly sneak up to people and… crack the confetti eggs on their heads!

Los amigos mejores son libros –

Books are your best friends

1

27-Pound Egg

Some people collect coins or stamps, but I collect socks. I have a dresser with drawers labeled DAILY SOCKS, LONELY SOCKS, HOLEY SOCKS, and SOCK HEAVEN.

The daily drawer helps me get dressed every morning. When I’m bored, I reorganize it. I group the socks by color. Then I group them by style—dressy, casual, or athletic. Then by length—ankle, crew, or knee-high.

The lonely sock drawer is for those who have lost their partners. Most of the partners disappear in the washing machine or dryer. I can’t explain it. Somewhere between the tossing and soaking and wringing, one gets lost. I don’t know where it goes. Maybe aliens abduct it.

Holey socks aren’t for angels. They actually have holes, so I don’t wear them anymore. Sometimes, these socks become puppets and sometimes they go to sock heaven where they can rest in peace with the socks I’ve outgrown.

But mostly, I use the holey socks for experiments. People who think socks are just for feet have no imagination. For example, you can cover your ears with socks. Ankle socks make good earmuffs. Knee-highs are great for people who want to be rabbits or donkeys for Halloween. Then there’s the sock rock. I’ve got a pile of these in a shoe box by my bed. I roll the sock and make a ball by folding the open end over the roll. Socks are also great as coasters, bookmarks, wallets, and dusters. There’s no end to what they can do.

I admit that spending so much energy on socks is weird and a little immature, but it’s hard to be normal when you live in a house with no TV. The reason I don’t have a TV is because my dad’s a high-school English teacher, which means he’d rather read. And because he’s always reading, I got stuck with a stupid name, Apolonia Flores. The Flores part isn’t so bad since it means “flowers” in Spanish. But Apolonia?

“What kind of name is that?” I ask my dad.

“It’s the girl form of Apollo,” he says. “He was the god of the sun. Get it? It’s my way of calling you a sunflower.”

“I’d rather be called Sun Flores. That’s close enough, don’t you think?”

But my dad doesn’t hear me.

“According to the Greeks,” he says, “the sun was the golden wheel of a chariot that Apollo drove across the sky. He was also the god of music, poetry, medicine, and fortune-telling.”

Whenever my dad speaks, I can’t help thinking that he looks like the teachers on Disney Channel specials—graying hair, lean body, wire-rimmed glasses. He always acts the part, even at home. It makes asking questions dangerous because something that takes most fathers five minutes to explain, takes mine an hour.

Thank goodness my name is too long, even for my father. Everybody calls me Lina instead. My dad says Lina sounds a lot like Leda, a girlfriend of Zeus, king of the gods. He disguised himself as a swan when he visited her, so now I’m named after someone who dated a bird.

Having an English teacher for a dad also means that instead of a dining room, we have a library, and instead of bedrooms, we have libraries, and we can probably call the kitchen a library too—even the pantry!—because next to my Pop-Tarts and Dad’s chicharrones are books.

And they aren’t in any order! The school librarian has the Dewey Decimal system, which makes finding books easy. But at my house, Dad’s got Be Your Own Handyman next to 100 Favorite Love Poems and Birds of North America next to Tex-Mex Cooking. So if I’m looking for a book on cats, I’ve got to read every title. This can take hours because Dad doesn’t have a pattern when he stacks the books. Some titles read top to bottom while others read bottom up, and the titles of horizontal books are upside down as often as they’re right side up.

Anyone can see the books are used. All the paperback spines are creased, and the hardback jackets, torn. The pages are yellowed, dog-eared, underlined, highlighted, and tagged with pink or lime green Post-its. Other than that, the books are clean, which is weird because my dad will forget to dust the coffee table long before he forgets to dust his books. He stands before a shelf with a rag, pulls out the books one by one, and wipes the dust off. This eats up hours.

“Why don’t you get rid of them?” I ask.

“Remember,” he says, “los amigos mejores son libros.”

This means that books are your best friends. In addition to quoting poetry, Dad likes to say dichos, Spanish proverbs. I’m not really bilingual, but I know that el gato dormido no caza ratón means “the sleeping cat doesn’t catch the rat” and that una acción buena enseña más que mil palabras means “actions speak louder than words.”

“Besides,” Dad says, “I’m a bibliophile. Biblio, remember, is the Latin word for ‘book,’ and phile is the Greek word for ‘lover.’ Put them together and what do you have?”

“Book lover?”

&

nbsp; “That’s right.”

“So does that make me a sockio-phile?” I ask.

One day, I tried counting my dad’s books but gave up around 600. I tried again, giving up at 923. I thought I could get my dad’s name into the book of Guinness World Records. I’d been reading it in the car every time Dad drove me to school or to volleyball games. I learned that the farthest human cannonball flight is 185 feet. If a football field is 300 feet, then imagine a guy flying over two-thirds of it. Wow! I also learned that the heaviest egg ever found was 27 pounds. More than two ten-pound bowling balls! It came from an elephant bird that went extinct a long time ago. I don’t know who has the most books, but I did learn that the most books typed backward is 58. Now that’s weird!

How can I not read when I live in a house with so many books? Sometimes I trip over one, pick it up, and before I can stop myself, I’m skimming the pages.

We have plenty of fairy tales and poems and big, fat books Dad calls epics, but I’m a facts-and-figures kind of girl. My favorite book is Gray’s Anatomy. It’s all about the human body. With my middle-school vocabulary, I can’t really understand all the words, but the pictures are great, especially the transparencies, clear pages that show the layers of the body starting with the bones, then the heart and lungs, then the stomach and intestines, then the muscles. I can look at those pictures for hours.

Yes, Gray’s Anatomy is a good book. It shows me how the body works. The only thing it can’t tell me is how the body doesn’t work. Believe me, I’ve looked. I’ve looked long and hard. Because I want to understand how my mom died last year. She was healthy, perfectly healthy, until she fell, cut her leg, and got a blood infection from something called staphylococcus. I didn’t understand it, any of it, but I sure tried.

A few months after the funeral, I asked my dad, “What’s a staphylococcus infection?”

“Well, m’ija,” he said with his teacher’s voice, “staphylo comes from the Greek word staphulē, which means ‘a bunch of grapes.’”

“But that doesn’t make any sense,” I said. “Are you telling me a bunch of grapes hurt Mom?”

He didn’t answer. For the first time, my dad didn’t answer. He just put down his head and cried.

Un amigo es el mejor espejo –

A friend is the best mirror

2

Egg Therapy

My dad started reading a lot more when my mom died. Sometimes when I dream about him, I see a body, a neck, and a book where his face should be.

“Are you okay?” I ask, peeking through his bedroom door.

“‘O, that this too too solid flesh would melt,’” he says.

Sometimes I can’t stand being in the house with my father so sad. Thank goodness Vanessa lives across the street. She’s been my best friend since forever. We play volleyball together. We do our homework. We talk about clothes, global warming, and boys. Ugly Betty is our hero. Our rule at restaurants is to eat the one thing we’ve never tried even if it’s tripas, a Tex-Mex dish made out of cow intestines.

We should be twins after all the time we spend together, and maybe we are twins, personality-wise. But in looks? Except for our brown hair and eyes, Vanessa and I are as different as a swan and an ostrich. She’s the swan, and I’m the ostrich. I’m really the ostrich—the tallest girl in class, all legs. Too tall and skinny for my jeans no matter what size I buy. Everything is high water. That’s why I’m a sockio-phile. I need something to hide my knobby ankles. Today my socks remind me of whitecaps on the ocean because they’re aqua with white lace around the cuff.

Vanessa doesn’t need a zillion socks. Everything fits perfectly—never too long or too short, too tight or too loose. And she never has a bad hair day. She could spend thirty minutes in front of a high-speed fan without getting tangles. If she wanted, she could make a paper sack look like something a model would wear.

I should be jealous, but I’m not. I don’t care about my looks. I care more about volleyball, geometry, and how toasters and lawn mowers work. But, I admit, when Jason Quintanilla called me Daddy Longlegs, I went to the girls’ restroom to cry. Not because I care what Jason thinks, even if he is the most popular boy in school, but because he called me Daddy Longlegs in front of Luís Mendoza, someone I do care about. Luís didn’t laugh at the joke, but he didn’t defend me either. He just stared at the sundial he wears on his wrist. I have such a big crush on him. How can I not like someone with a sundial instead of a normal watch? And he really can tell time when it’s not rainy and cloudy, and that’s almost always in Corpus Christi, Texas.

Of course, Vanessa knows all about my crush on Luís, since it’s my favorite topic of conversation. And I know all about her crush on a guy named Carlos.

I decide to get out of my house and walk across the street to Vanessa’s. When I see her mom through the front screen door, I tiptoe to the backyard.

“Hey, Vanessa,” I call through her bedroom window.

She’s on the phone. She says, “Can I call you back later? Lina’s here—yes, I promise—ditto—you know I do. Do I have to say it?” She cups her hand over the receiver and whispers, “I love you, too.” Then she hangs up.

“Who was that?” I ask as she holds open the screen so I can climb in.

“My dad. You came just in time to save me from apologizing to his girlfriend. I guess I hurt her feelings.”

“How?”

“I called her a Windsor and then I told her what it means.”

If that’s true, then Vanessa told her dad’s girlfriend that Windsor means more purses and shoes than brains. It’s a word Vanessa and I made up. We use it when we’re talking about stuck-up girls who think they really live in Windsor Castle.

Vanessa has two beanbags, one blue and the other red. I plop onto the blue one as if I own it, and in a strange way, I do. I didn’t buy it and Vanessa never officially gave it to me, but the blue beanbag’s mine—my little corner in her room. When she goes to my room, she hangs out on the top bunk.

“Why were you at my window?” Vanessa asks. “Is something wrong with my front door?”

I don’t answer right away. How can I tell her I’m avoiding her mom? Especially when Ms. Cantu is such a wonderful woman? She’s shown me so many grown-up things over the past year about washing clothes and cooking, things my mother was just starting to teach me. She even buys me girl stuff from the grocery store, Clearasil and Kotex, because I’m too embarrassed to remind my dad. I should be glad to see Ms. Cantu, but every time I do see her, she hugs me and calls me pobrecita and makes me feel like an orphan.

“I didn’t want to bother your mom,” I say to Vanessa. “She’s been so busy.”

“Tell me about it. Guess what I had for dinner last night.”

“Eggs?”

“And for lunch today.”

“More eggs?”

“That’s right,” Vanessa says. “How many times can you eat scrambled eggs without scrambling your brain?”

Around Easter, most people hard-boil eggs before painting them with dyes made by dissolving colored tablets in hot vinegar. But in Texas, we make cascarones, confetti eggs. Instead of hard-boiling eggs, we carefully crack open a small hole on the top and let the insides spill out. Then we wash and dye the eggshells. After they dry, we stuff them with confetti and glue a circle of tissue over the hole. On Easter morning, we run around and crack the eggs on each other’s heads. Confetti gets everywhere. It’s a lot of fun.

Everybody loves cascarones around Easter time, but Ms. Cantu has made them a yearlong event. That’s why poor Vanessa lives with mountains of eggs. They’re everywhere—eggshells stacked on the kitchen table, above the fridge, on the couch—some blue, orange, or pink, and some still white—and next to the eggs are circles of tissue paper and piles of magazines and newspapers because Ms. Cantu believes in making her own confetti with a hole puncher.

“If only eggs made us better at volleyball,” I say. Vanessa and I play for our school, but our team isn’t very good.

> Vanessa laughs. “Maybe we’d win a few games.”

“If that were true, I’d come over and eat eggs all the time.”

“I’d feed them to the whole team.”

“I don’t know what’s crazier,” I say, “reading all day like my dad or making cascarones like your mom.”

“She calls it ‘therapy.’ I guess she’s upset because my dad has a girlfriend. I don’t know what the big deal is. It’s time to move on. My parents have been divorced for three years.”

“Maybe your mom thought he’d come back.”

“But she doesn’t want him back. She’s a man-hater. When she isn’t making cascarones, she’s watching telenovelas or the Lifetime Channel. All the stories are about rotten men who cheat on their wives.”

“Well, my dad’s not rotten,” I say.

“Neither is mine, but try telling her that.” Vanessa grabs a heart-shaped pillow and hugs it. “How’s your dad doing?” she asks.

“I don’t know. He can’t talk without quoting some book or saying some dicho that doesn’t make sense.”

“It can’t be worse than a mom who keeps making cascarones. Easter was five months ago!”

“At least she’s not saying her flesh is going to melt.”

“At least you don’t have to eat your dad’s version of therapy.”

“What are we going to do?” I ask. “Our parents are so miserable.”

“Don’t worry,” Vanessa says. “We’ll think of something.”

Querer es poder –

To desire is to be able to do

3

Don’t Put Your Eggs in One Basket

Baker is our middle school, a brick building in a neighborhood with street names like Casa Grande, Casa Linda, Casa de Palmas, and our street, Casa de Oro, which means “house of gold.” I felt nervous about starting middle school, but then I realized I could sign up for sports. During recess in elementary school, I was always the first girl that got picked for teams. I got picked before most of the guys because I was just as tough and fast. So Vanessa and I signed up for volleyball on the first week of school. For now, we have to play on the B-team, but if we’re good enough, we’ll get to play on the A-team next year.

Coco Middle Grade Novel

Coco Middle Grade Novel Ask My Mood Ring How I Feel

Ask My Mood Ring How I Feel Choke

Choke Confetti Girl

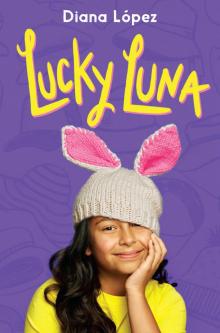

Confetti Girl Lucky Luna

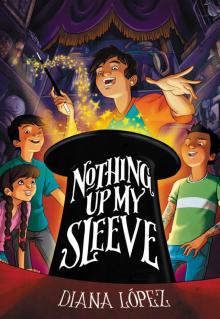

Lucky Luna Nothing Up My Sleeve

Nothing Up My Sleeve