- Home

- Diana Lopez

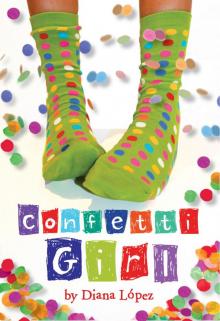

Confetti Girl Page 4

Confetti Girl Read online

Page 4

“Sure,” I tell her. “No problem.” But it is a problem because I look in the fridge and see that Dad used all our potatoes last night.

“What do I do now?” Vanessa cries. “I can’t let Carlos know that I put Duchess in danger. We’ll get an F and he’ll never talk to me again.”

Usually, she looks at the ceiling and touches her chin for the answer. But not today. I’ve never seen her so stressed. I’ve got to calm her down before she pulls out a clump of hair and goes bald. I make her sit and serve her a glass of water. Then I go to the backyard and search for potato-size rocks, finding four near the fence. With a little reshuffling, we manage to hide them in the potato bag. Duchess is as good as new.

“You’re a genius,” Vanessa says. “I don’t know what I’d do without you.”

I take a bow. “Best friend, at your service.”

En boca cerrada no entran moscas –

Flies can’t enter a closed mouth

7

Scrambled Eggs for Brains

A week later, we have our last volleyball game. Our team didn’t make it for district finals. Big surprise. But we’ve got one more game, and we’re going to finish with dignity.

“Because,” Coach Luna tells us in the locker room, “sometimes you win, sometimes you lose, but never, ever, ever do you quit. Besides, the A-team coach promised to watch. She wants to recruit players for her team.”

With that, she sends us to the gym to warm up. My dad’s already there. He waves and does a little mime to say, “Look! NO BOOKS!” I give him a happy thumbs-up to show my approval. Then Ms. Cantu enters the gym. She walks straight onto the court, magically dodging stray balls.

“I’m wearing a special game shirt for you,” she tells Vanessa. It’s a red extra-large T-shirt. She sewed on a big, felt volleyball, painted Vanessa’s number on it, and randomly glued a few stars. It’s tacky but sweet. “I’m here for support,” she adds, “but if your dad shows up with that girlfriend of his, I’m leaving.” With that, she does an about-face and heads to the bleachers, spotting my dad and taking the seat beside him.

Ms. Cantu and my dad get along okay. All their conversations are about Vanessa and me—and sometimes my mom. I doubt they have real heart-to-hearts, but they’re close enough to call each other by their first names—Irma, pronounced “ear-ma” with a little roll on the r—and Homero, also pronounced with a little r-roll.

This time we’re playing against Tom Brown Middle School. I’m not really nervous about losing, even though it’s a real possibility. I’m more nervous about playing in front of the A-team coach. I really want to make a good impression. Maybe I can get permission to practice with the A-team during the off-season. I hear they sometimes work with B-team players who show a lot of potential.

When the game starts, I dive for balls and risk more volleyball slaps when I block the spikes. We win one. Tom Brown wins one. So we get the third tie-breaking game. It’s close. The serve goes back and forth. We’re never more than two points apart. I’m doing my best, really shining, because the A-team coach is taking notes and my dad’s here without a book. Vanessa’s doing her best too because her mom’s actually taking a break from cascarones and telenovelas. In fact, I’m too focused on my game to notice that Luís isn’t at the popcorn machine. When I do notice, I figure he’s in the bleachers, do a quick scan, and realize I’ll never spot him because everyone’s here—all the teachers that have been promising to come and lots and lots of students.

Their energy feeds us. We’re hyped. We’ve got the hopes of all our friends, teachers, and parents on our shoulders, and we don’t want to disappoint.

Amazingly, we win. Coach Luna jumps up and down, cheering, and giving all of us high fives.

After getting my things from the locker room, I find my dad.

“Lina,” he says, waving me over, “I was just talking to Mrs. Hammett.”

She’s the A-team coach, a real coach with tennis shoes and polyester shorts.

“It’s a pleasure to meet you,” she says. “I was just telling your dad that you should join the A-team at volleyball camp next summer.”

“Really?” I can’t hide my excitement.

“Here’s a brochure,” Mrs. Hammett says. “There’s a good camp at the University of Texas in San Antonio every summer. You’ll get to stay in the dorms for two weeks, and you’ll meet girls from all over Texas.”

“Can I go, Dad?”

“As long as you keep up your grades.”

“Oh, I will. I promise,” I say. “Can I have an extra brochure, Mrs. Hammett? I’d like to give one to my best friend, Vanessa.”

“Sure,” Mrs. Hammett says. “Here are a few extra. Pass them along.”

We thank her, and she leaves to speak to the Tom Brown coach.

“Look what I have,” I say when I find Vanessa and her mom in the parking lot outside the gym. “It’s information about a volleyball camp next summer.”

I hand the brochure to Vanessa.

“This looks like fun,” she says. “Can I go, Mom?”

“Only if your dad’s footing the bill. Money doesn’t grow on trees, you know. At least not on my trees.”

The next morning, Dr. Rodriguez announces our volleyball win over the intercom. Since Goldie and I are in Miss Luna’s first-period class, she makes everyone applaud. I feel like a real Hollywood until I see Jason crossing his arms instead of clapping.

“Just because you won one stupid game,” he says, “doesn’t mean you’re in the Olympics.”

“Chill out,” I say. “No one disses the football team because they get pep rallies and cheerleaders and candy bags in their lockers on game days.”

“That’s right,” Goldie adds. “It can’t be all Jason all the time.”

Even with Jason in the room, I enjoy math. My answers are right or they’re wrong, no gray area, no guessing games. This week we’ve been learning how to calculate distance, and Miss Luna wants us to write a word problem using the equation “distance equals rate times time.” I decide to add a few colorful details to mine.

After everyone stops scribbling, Miss Luna asks us to share our word problems.

One of my classmates says, “If a blue car travels eleven miles per hour for two hours, how far has it gone?”

“Twenty-two miles,” we all answer.

“If a red car,” the next person says, “travels twenty miles per hour for three hours, how far has it gone?”

“Sixty miles.”

“If a green car…”

“I can’t take this anymore,” I say. “Did everyone write about cars?”

“Not me,” Goldie says. “I wrote about a bowling ball.”

“Let’s hear your word problem then,” Miss Luna says.

“If a bowling ball travels ten feet per second for three seconds, how many feet has it gone?”

“Thirty feet,” we all answer.

I love Goldie, but her bowling ball problem is just like everyone’s car problem.

Finally, it’s my turn. I stand up and clear my throat.

“A football player named Jason stuffs his face with three hot dogs before the game and gets severe stomach cramps during the second quarter. At the rate of five yards a second, he runs forty yards before he has to throw up. How long does it take for him to reach his upchuck zone?”

The whole class cracks up and I take a bow. But Jason isn’t amused. When class ends, he “accidentally” bumps into me.

“So,” he says, “can you really bend your knees backward?”

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

“Whoop! Whoop!” he says, urging his friends to join him.

“What’s wrong with you? You’re acting like retards.”

“Whoop! Whoop!” they say again.

“I think he’s making fun of your science topic,” Goldie says.

“What do whooping cranes have to do with anything?”

“They’re tall,” Jason explains, “ridiculously and uselessly tall!”

He and his friends walk off, laughing harder than tickled babies. When they reach the end of the hall, I hear the “Whoop! Whoop!” again. Last month, I was a daddy longlegs spider; this month, I’m a bird, a ridiculously tall bird.

“How’d he find out about my science topic?” I ask Goldie. “He isn’t even in my class.”

“I don’t know,” she says.

I stomp to the restroom and grab a bunch of paper towels. Shredding them doesn’t solve any problems, but it sure helps me deal with my anger.

When I get to Mr. Star’s room, I see a chart with our names and projects. There are other charts, too, for other classes. Jason’s class is studying animal family structures. He gets to do a report on lions. How do you make fun of lions? And why do whooping cranes have to be so tall?

“Hi, Vanessa,” I say when she comes in.

She waves, but instead of coming to her desk, she goes to see Carlos. She’s been talking to him a lot lately, and sometimes she doesn’t notice I’m around.

Lucky for me, Luís comes in too. He sits in front of me and claps his hands.

“What’s that for?” I ask.

“The g-g-game. I heard the announcements.”

“Oh, thanks,” I say. Then I realize he didn’t know about our win until this morning. “Why didn’t you go?”

“You see, I was uh, uh, trying out for the Christmas concert.”

“That’s great,” I answer, thinking that a boyfriend who played an electric guitar or the drums would be cool. “What instrument do you play?”

He shakes his head.

“You don’t play an instrument?”

He nods.

“So you’re going to be part of the stage crew?” I say. “That sounds like fun. You get to design stage sets and work the spotlight and control the curtains.”

He shakes his head again. He’s about to speak, but I can’t help babbling.

“You didn’t make it?” I say. “Well, if you ask me, they’re the ones missing out. Like I said, you’d be great at stage design. It takes a real artist for that.”

He looks at his feet. His glasses slip down his nose. His curls fall forward.

“What’s wrong?” I ask.

“You don’t get it.”

He sounds seriously mad—mad enough to forget stuttering. He takes one look at me, shakes his head, and turns away. He’s right. I don’t get it. What did I do wrong?

The bell rings, and Mr. Star says, “Vanessa, Carlos, get to your seats now.”

I hear her settle in behind me. I should tease her about Carlos, but I’m too preoccupied by Luís. I take out a sheet of paper and write a note.

So what did you try out for? I ask. I fold it into a neat paper football and wait for Mr. Star to turn his back before passing it forward.

Luís slowly unfolds it. Then he bends forward to read it. A long time passes before he crumples it up. He keeps it in his hand, his fist tight around it. After another long time, he opens it up again and writes something back. His pencil’s loud. I imagine him scraping his desk. He crumples the letter again and tosses it over his shoulder. It hits me on the chin and falls on my lap.

I open it, not knowing what to expect, and there’s my answer, in all caps and with lots of exclamation points.

I TRIED OUT FOR CHOIR, YOU DUMMY!!!!!!!!

I’ve really got scrambled eggs for brains sometimes.

Dime con quién andas y te dire quién eres –

Tell me who you hang out with and I’ll tell you who you are

8

Cascarones War

Now that it’s Halloween, I can’t wait to show Vanessa my costume. We don’t go for the cheap, polyester, one-size-fits-all costumes at Party City or for the expensive rentals at Starlight Ball where the outfits are good enough for Harry Potter movies… or real aliens. No, Vanessa and I believe in the homemade stuff. So I put on my red warm-ups and red slipper socks. I hide my hair in a red knit cap. I paint my face red and drape artificial ivy over my shoulders. And I’ve got my sign with pictures of fish, black X’s over their eyes, and tombstones with S.I.P. for “Sink in Peace.” Mom would have been proud. She’d say the costume is perfect and totally me and that no one else could have imagined such a unique idea. And, she would’ve guessed what I was, no problem. But my dad is clueless.

“So what are you?” he says. “No, no. Let me guess.”

I turn around. Then I turn around again. I can’t believe it’s taking him so long to figure it out.

“Oh, I get it,” he says. “You’re a fish devil.”

I’m too shocked by his ignorance to speak. I’m about to explain my real identity when the phone rings.

“We’re ready,” Vanessa says.

My dad and I walk across the street. As soon as Vanessa sees me, she says, “That is so totally cool, Lina! You’re like Nemo’s version of Satan.”

I can’t believe it. Even Vanessa gets it wrong, and she’s in my science class!

Ms. Cantu comes to the door. She’s got on a black T-shirt with a huge, happy-face pumpkin. She turns around. On the backside, the pumpkin face makes Freddy Krueger look like a teddy bear.

As soon as she finishes modeling, she twirls her finger and says, “Now it’s your turn, Lina.”

I turn around.

She’s a little confused at first, but then she gets this glimmer in her eye. “¡Qué chula!” she says.

“Mom!” Vanessa says. “Lina’s not trying to be cute. She’s trying to be evil and sinister. She’s a fish devil. Get it?”

“Fish devil?”

“Sure, what did you think she was?”

Could it be? Is Ms. Cantu the only one who understands my costume? Who actually gets me?

“I thought she was shrimp sauce,” she says.

“Shrimp sauce?!”

We crack up. All of us. All at once. I give up. No one will ever get my costume.

After we get over the giggles, we load the truck with boxes and boxes of cascarones for the Halloween carnival. Ms. Cantu has made special eggs for the event. Using a white crayon, she drew different pumpkin faces on the shells. Then she dyed them orange. The wax from the crayon keeps the dye from sticking, so the eggs look like miniature pumpkin heads.

Every now and then, Vanessa stops to re-stuff herself. She’s dressed as a scarecrow. She’s wearing one of her father’s flannel shirts and torn-up jeans. For hay, she’s used ojas, corn shucks for steaming tamales. She’s got them sticking out from her collar and cuffs and between the shirt buttons. She’s also glued them along the inner rim of a cowboy hat. I think she’s done a good job of making her hair look like hay.

The carnival is held in the school cafeteria and the courtyard. Goldie and some of the other girls have already decorated our booth with streamers and cutouts of pumpkins, black cats, witches, and ghosts. The sign says, CASCARONES: 20 CENTS EACH OR $1.50 A DOZEN. My dad and Ms. Cantu are the adult chaperones so they’ll stay at the booth all night. The rest of us will take turns. Vanessa and I take the first shift.

A few people walk by, see the cascarones, and move on.

“I don’t know,” Vanessa says. “Maybe this was a bad idea.”

“Are you upset about losing money or having to take the eggs back home?”

“Losing money and taking back the eggs,” she says.

Eventually someone stops at the booth—Sum Wong, who likes to be called Sammy. I’ve known Sammy since the fourth grade.

“I like your fish devil costume,” he says.

“I’m not…”

“So what’s with these eggs?” he interrupts. “Is this some kind of Latino thing?”

“Yeah,” Vanessa says. “You’re supposed to sneak up on people and crack the eggs on their heads. All this confetti comes out. It’s lots of fun.”

“Really?” He raises an interested eyebrow, then reaches in his pocket for some money. He spends a long time staring at the carton, finally picking an egg with an evil-looking expression. He walks straight to a pep squad gir

l in front of the taquito booth and CRACK! breaks the eggshell on her head.

She shakes off the confetti. “Sammy!” she yells as he runs to hide. “I’m going to get you!” She marches to our booth, pays for an egg, and runs off. A few minutes later, Sammy comes back for a dozen more. Before we know it, we’ve got a line. It’s a cascarones war out there.

“This is wonderful!” Ms. Cantu says. “This proves my theory. Cascarones are fun all year long!”

My shift is almost over when a guy from my history class, Jorge, walks up. He’s dressed as a policeman.

“Sorry, Lina,” he says. “But I’ve got a warrant for your arrest.”

“I can’t go to jail,” I say. “I was just getting ready to start enjoying the carnival.”

“Rules are rules,” he says.

“Go on,” Vanessa says, “I’ll get you out as soon as I’m finished here.”

What a bummer, I think, but Jorge is right—rules are rules—someone paid fifty cents to put me in jail and someone else has to pay fifty cents to get me out.

The jail booth is outside in the courtyard. It has bars over the window, two benches, and a guard dressed as a mariachi. There’s one prisoner, Sammy Wong.

“I guess the pep squad girls got tired of getting confetti out of their hair,” he explains.

I take a seat to wait for Vanessa. Five minutes go by, nothing. Ten minutes, nothing. Where is she? Aren’t friends supposed to look out for each other? When one of Sammy’s friends pays his bail, I get more impatient.

“Okay, Lina,” Jorge finally says. “You’re free to go now. That guy over there paid your bail.”

He points across the courtyard where Luís is leaning against the tree. He’s holding a headless Superman piñata. He’s wearing a neon green T-shirt with a bright yellow “K.”

I’m a little nervous when I approach him because we haven’t spoken since our misunderstanding about the Christmas concert tryouts. Every day in science, I think about saying something, but I’m too scared. He probably hates me.

“You either have a really bad memory or a very forgiving heart,” I say.

Coco Middle Grade Novel

Coco Middle Grade Novel Ask My Mood Ring How I Feel

Ask My Mood Ring How I Feel Choke

Choke Confetti Girl

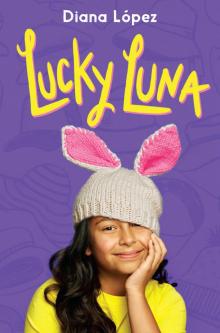

Confetti Girl Lucky Luna

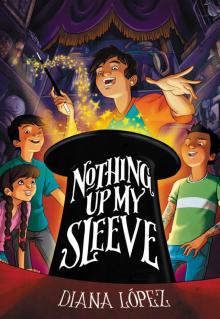

Lucky Luna Nothing Up My Sleeve

Nothing Up My Sleeve