- Home

- Diana Lopez

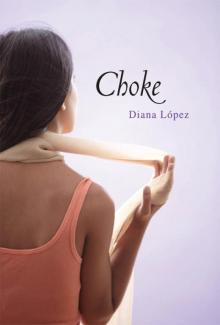

Choke Page 6

Choke Read online

Page 6

Okay, maybe his hair wasn’t as bright as Ronald McDonald’s, but when I got mad, I tended to exaggerate.

I finished my list just as we got to Elena’s house. As soon as Dad turned off the car, she said, “I’m going to ask if I can go to the mall with you guys.” Then she sprinted to her door.

“I thought her grandma was coming over,” I said. I didn’t intend to sound eager to leave her behind, but that’s how it came out. Besides, I had spent the whole night and most of the day with her. Now it was time for me to spend time with Nina. How did that saying go? “Two’s company but three’s a crowd.” That was how I felt when Elena was around because every time I tried to be cool, she always said something nerdy.

Dad opened the trunk, and we grabbed some of Elena’s things. A minute later, she came back out. She wasn’t sprinting anymore. She walked like someone giving a piggyback ride to a laundry bag full of wet towels.

“My mom said no,” she told us as she brushed by.

Elena’s mom held open the door so we could put the bags inside. Soon Elena returned with the rest of her stuff.

“I hate when Grandma comes,” she mumbled. “It’s not like she talks to me or anything.”

“Young lady,” her mom warned.

“Well, it’s true. She can barely hear anything.”

“She can hear well enough. You just have to look at her when you speak.”

My dad, Nina, and I stood around. Nothing was more uncomfortable than watching someone else’s family squabbling.

“Thanks for bringing her home,” Mrs. Sheppard said.

“My pleasure,” Dad answered.

“Bye, Elena,” I called. “We’ll catch you next time.”

She gave me a halfhearted wave good-bye, and then turned away.

She seemed mad at me. She was mad at me. After all these years of friendship, I could tell. What was the big deal about missing one afternoon?

Dad left Nina and me at North Star Mall. Nina’s mom was going to pick us up and take me home. I couldn’t wait to meet her. She was probably double cool, unlike my silly-looking dad.

“I hope you don’t think my dad’s weird,” I told Nina as he drove off.

“Why?” she asked. “Because he lightened his hair?”

I covered my face with my hands, all embarrassed.

“I thought your dad’s hair looked great,” Nina said.

“Really?”

“Yeah. At least he has hair. My dad is going bald.”

“Thing is,” I said, “my dad never cared about the way he looked. Now, all of a sudden, he’s obsessed about it. It wouldn’t bother me if he’d let me bleach my hair.”

“Why would you want to bleach it? Your hair looks beautiful just the way it is.”

“You really think so?”

“Would I lie to you?” She looked straight into my eyes.

“No,” I answered. “I guess not.”

“So it’s settled then. You’ve got good hair.”

Part of me didn’t accept this. I always thought my hair was a frizzy, tangled mess. But as we approached the glass door to the mall, I saw my reflection. My hair was a deep brown and full-bodied. Maybe it did look beautiful — kind of.

We stepped into the mall and a cold blast of air hit our faces.

“Come on,” Nina said. “Let’s eat. I’m starved.”

We went directly to the food court and ordered Chinese from Panda Express. Nina got rice with sweet and sour chicken, and I got rice with sweet and sour pork.

We found a table and started eating. Then I opened my TOP FIVE notebook so we could make lists — The Top Five Toppings for Ice Cream, The Top Five Coolest Colors for Tennis Shoes, The Top Five Grossest Things to Find Beneath Your Fingernails, The Top Five Uses for a Packet of Ketchup, and The Top Five Embarrassing Things People Do in a Food Court When They Think No One’s Looking.

“I’m going to get a refill,” I said. “Would you like one?”

“Sure.” Nina handed me her cup.

When I returned, she quickly closed my notebook.

“Did you make another list?” I asked.

“No. But I found one that wasn’t finished, so I added to it.”

I riffled the pages to find it. I couldn’t believe I’d left an incomplete list.

“You can read it later,” she said. “I’ve got a cool idea.”

“Really? What is it?”

“Let’s get makeovers.”

Our drama teacher had two masks at the top corners of her door. I could feel those masks on my face as I went from smiling to frowning. “My parents don’t want me to wear makeup yet,” I said. “I’ve got to be in high school first.”

“It’s just for today,” she said. “You can wash it off before you go home.”

She was right. I could always wash it off. If Dad could try a new hair color, then I could try a little makeup. It was only fair. Besides, getting a makeover sounded like a lot of fun. Elena never had good ideas like this.

We went to Dillard’s. As we walked through the cosmetics department, a lady offered to squirt us with perfume, so we held out our wrists. The mist was cool, and I liked the floral scent even though it made me sneeze.

“This is really expensive,” I said, glancing at the prices on the makeup containers.

“Don’t worry. My treat.”

“Oh, no. I couldn’t, Nina.”

“It’s not a problem. I owe you, remember?”

“For what?”

“For being my friend. I was the new kid at school, and you made me feel right at home. I was really lucky to meet you.”

Wow! Her compliment put me on cloud nine. If I kept hanging out with Nina, I’d be in the in-crowd before the semester ended. I just knew it.

“I guess you can treat me, then,” I said. “But let’s look at the clearance or the discontinued stuff.”

Nina agreed and bought me a brown eyeliner, a very natural-looking lip gloss, a compact that was the exact shade of my skin, and a bottle of clear polish for my nails. The total was over $20, but she paid. I figured her parents must have a lot of money.

“Let’s go to the restroom,” Nina said, heading to the hallway behind the customer service counter.

The restroom at Dillard’s had a parlor with a small sofa, a coffee table, an arrangement of fresh flowers, and a huge gold-framed mirror. Another door led to a room with silver stall doors, and sinks that were nestled in a black marble countertop that almost looked like a mirror because it was so clean. The whole place smelled like lavender. And everything was no-touch. Just wave the hand beneath the faucet for water or under the dispenser for soap.

First, I washed my face. Then we sat on the sofa in the parlor. Nina took the compact and brushed the powder onto my face. It tickled the way Raindrop’s fur tickled when he nuzzled against my neck. Next, she told me to close my eyes as she applied the eyeliner. I could feel her body warmth as she leaned close and smell the perfume that lingered on her wrists. Finally, she handed me the lip gloss, telling me to use just a little bit.

“You look great,” she said.

I looked at my reflection in the mirror. I did look great. Nina was right, again. My skin looked smoother, my lips fuller, and my eyes more defined.

“You think Ronnie will notice?” I asked.

“Are you kidding? He’s been noticing you all week.”

It was true. Ever since our conversation at the bus stop, Ronnie had found me in the cafeteria or hallway and talked to me. A lot.

“Let’s do your nails,” Nina said.

She took a file from her purse and shaped my nails, rounding the edges and making them all even. Then she opened the bottle of clear polish. For a while, the chemical smell overpowered the lavender, but I got used to it. Nina took the little brush and swept it over my nails. Then she blew on them, her breath like autumn’s first cool front, the one that reminds you that the sweets and gifts of Halloween and Christmas are only a few weeks away.

I knew it was a

stupid question, but I had to ask. “Is this how you become a breath sister?”

She laughed a little, and I felt like a kid who still believes thunder is the sound of angels bowling.

“I thought you knew what a breath sister was,” she said.

“I do. It’s like being a blood brother, right?”

“The concept’s the same.”

I stared at her, waiting for more.

She stopped blowing on my nails but still held my hands. Then she asked, “Have you ever heard of the choking game?”

I know about metaphors. We talk about them in English class. Metaphors happen when people say something that really stands for something else. Like when you say “letting the cat out of the bag” or “spilling the beans” instead of “telling a secret.” There isn’t a cat in a bag, and there aren’t any beans on the ground. It’s all figurative. So I thought that “choking game” was a metaphor. But it wasn’t.

“It’s got other names,” Nina said. “Like Knockout Game, Wall Hit, Airplaning, Rocket Ride.”

“I’ve never heard of them.”

“How about Sleeper Hold, Pass-Out Game, or Cloud Nine?”

I shook my head to all of these.

“I can’t believe it,” she said, laughing. “Where have you been all this time?”

“Hanging out with Elena,” I said.

“Oh, right. Hanging out with Elena.” The way she said it made it sound like hanging out with Elena equaled playing on the merry-go-round — which made sense, since it was true.

“So what’s it like?” I asked. “This choking game?”

“You want to try it?”

“Will it make us breath sisters?”

“For life,” she said.

“Okay, then. Let’s do it.”

“First you have to swear to secrecy,” she said. “I already got kicked out of school for this, so you can’t tell anyone — not even Elena.”

I had to think a moment because Elena and I tell each other everything, even our dreams, no matter how strange. Like the time I dreamed Courtney and Alicia were pointing at me because I went to school as the Statue of Liberty, and like the statue, I was frozen, so I couldn’t speak or throw away the torch and crown. Then Courtney painted embarrassing graffiti on me, and everyone laughed. When I told Elena, she didn’t think I was weird or say that my dream was one big freak-o-rama. She listened. She said she had bad dreams about Courtney and Alicia, too.

I had never considered keeping a secret from her. But all of a sudden, I didn’t want to tell her everything. I knew I’d keep the choking game private because I wanted to share something with Nina, with only her.

“I promise not to tell,” I said.

Nina smiled, picked up our things, and led me to the restroom, checking beneath the stalls to make sure we were alone. Then we went to the largest stall, the one for ladies in wheelchairs. Nina secured the latch and looped our purse straps on the door hook.

“The choking game’s about trust,” she said. “So you have to trust me.” She put her hands on my shoulders, and looked me straight in the eyes. “Do you trust me with your life?”

The daredevil feeling that came from walking through the park at night or racing my bike down a steep hill washed over me.

“Yes,” I said. “Do you trust me?”

“One hundred percent,” Nina replied.

“Then teach me how to play the choking game.”

She took my hand and placed my fingers on the side of my neck.

“Feel that?” she asked.

I felt my skin’s warmth and my pulse.

“It’s like a water hose in your neck,” she said. “When we play the choking game, we pinch off the flow.”

I backed up a few steps. “You want to strangle me?”

“Windy.” She laughed. “What did you think? It’s called the choking game.”

“But …”

“You’re not going to get hurt,” she said. “I’ve played it lots of times. Do I look hurt to you?”

I shook my head. “But people die from being choked.”

“Only if you keep holding on,” she said. “That’s why we have to trust each other and let go before the game goes too far. That’s what makes us breath sisters — we put our lives in each other’s hands. Can you think of a better way to prove your friendship?”

Her explanation made sense. Then again, I never had to prove my friendship to Elena, so why did I have to prove it here?

“You can tap out whenever you want,” Nina said.

“What does that mean?”

“If you want me to stop, you can tap my arm and I’ll let go.”

Just then, we heard someone come into the restroom, and Nina made the sign for keeping quiet. The interruption gave me time to think about what it meant to be a breath sister, to become one, which made me think about the way blood brothers would take a knife, slash their palms, and shake hands. That had to hurt, not to mention all the germs. At least you didn’t bleed when you played the choking game. So how bad could it be? And if other girls were doing it, then it must be okay. Plus, it gave you a really special friend, an in-crowd friend.

As soon as the lady washed her hands and left, Nina said, “You don’t have to play if you don’t want to, but it’s the only way we can be official breath sisters.”

I felt scared, but even though I knew I might get hurt, a sense of adventure kept me going. “I know,” I said. “I thought about it. And I’m ready.”

She smiled. “Just remember, you can tap out whenever you want.”

“Okay,” I said.

Nina approached me, and I felt a little sick — like before a presentation in speech class. But I really wanted to do this, so I took a deep breath and nodded to give her the okay. She pressed her hands on both sides of my neck and started to squeeze. Just a little at first, but when I didn’t stop her, she squeezed tighter. I smelled the perfume on her wrists again, but since it’d been there for a while, it seemed sour now. Then I felt her breath, a light breeze, and I liked it, liked being close to her even if it meant playing this weird game. Then she squeezed my neck even tighter. It didn’t hurt but I felt pressure in my head like when I used to hang upside down on the monkey bars too long. Then the pressure started to balloon, especially behind my eyes. Was my head going to explode? Because that was how it felt. I started to panic. Let go! I tried to say. But I couldn’t because my voice was choked off, too. Then a bunch of green dots appeared. I knew I’d faint if I didn’t tap out. So I slapped at Nina’s forearms, and immediately, she let go — just like she promised.

I gasped and waved her off.

“You did great,” Nina said. “Maybe next time you’ll go all the way.”

I couldn’t speak yet, so I gave her a questioning look because I wanted to know what “all the way” meant.

“You’re supposed to pass out,” she said. “That’s how you get the rush.”

“What rush?” I managed.

“That high, floaty feeling. That’s why people play this game.”

I rubbed my neck. I could still feel the heat and pressure from her hands.

“Stay here,” she said. “I saw a vending machine outside. I’ll go get you some water.”

I could have waited in the parlor, but I was too afraid to leave the stall. People would see me, and they’d know what I’d been up to. I took out the compact Nina bought me and looked in the mirror. My neck was red, but already, the redness was going away. After a few more minutes, I could hide my act from the world and erase every trace of the choking game.

The only thing I could not erase was how I felt. As soon as I left the restroom stall, I’d be leaving a version of myself behind — because — because I was different now. I’d changed, like the way I’d changed after my first day in kindergarten or after Cyclone, my first cat, died. The way I imagined I’d change if I ever got to kiss Ronnie or drive a car. I felt smarter now, more grown-up.

Finally, Nina returned with a bottle of

water. She even opened it for me. I nearly drank the whole thing.

“Are you okay?” she asked.

“Sure,” I said, wishing I sounded more confident.

We left the restroom. Nina carried my purse and the bag of new makeup. I felt so confused. I really wanted to be Nina’s friend. I didn’t like the choking game, but everything else we did was fun.

“How many times do I have to play the choking game?” I asked.

“You don’t have to play again if you don’t want to,” she said. “Do you want to?”

I shook my head. “Do you play a lot?”

“Not a lot. But sometimes.”

I rubbed my neck. It felt a little sore.

“Hey, I’ve got another great idea,” she said. “Since we’re breath sisters now, let’s buy matching scarves.”

I brightened up. “You mean it?”

“Yeah. It’ll be so cool. We can wear them on the same day.”

I must have smiled really big because she grabbed my hand and pulled me to the accessories department. There were two aisles of beautiful scarves — some with fringe, some with sequins, some with detailed patterns, others with no pattern at all, just solid color. Choosing a design was tough, but since we didn’t have a lot of money, we settled for scarves from the discount bin, finding two yellow ones that were a complete match.

After we paid for them, Nina said, “This day has been so much fun, Windy.”

When I heard this, I didn’t feel confused anymore. Nina was my friend now — more than that, my breath sister.

We better hurry,” Nina said, “or we’ll miss our buses home.”

Buses? That wasn’t part of our plan. “I thought your mom was going to pick us up,” I said.

Nina laughed as if I’d made a joke.

“What’s so funny?” I asked.

“Don’t you remember, Windy? I’m grounded. I’m not supposed to be at the mall today. I’m supposed to be volunteering at the old folks’ home.”

I remembered now. She had told me she was grounded. But she said she was grounded from sleepovers. She hadn’t mentioned the mall.

“My parents think your mom’s picking us up,” I complained. “They think they’ll meet her.”

Coco Middle Grade Novel

Coco Middle Grade Novel Ask My Mood Ring How I Feel

Ask My Mood Ring How I Feel Choke

Choke Confetti Girl

Confetti Girl Lucky Luna

Lucky Luna Nothing Up My Sleeve

Nothing Up My Sleeve